Invisible Citings, 2014–17 Elaine Reichek Click on images to view project. |

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||||||

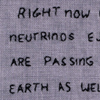

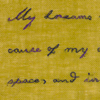

Invisible Citings is a collaboration with artist Jeanne Silverthorne, exploring text and invisibility. Situated at the alleged end of the Gutenberg age, when digital technologies strive to replace paper with glowing screens, our project considers the persistence of analog productions of language, and the physical manifestations of writing as material and medium. Through sculpture, embroidery and literature, we address themes of legibility and concealment, text and textile, storage and redaction, illumination and luminescence, archiving and discarding. For this project Jeanne made numerous rubber casts of a standard cardboard file storage box, and filled each box with a ream of apparently blank letter-sized paper. On many of these sheets, however, Jeanne had hand-copied a text in invisible ink, concerning some theme of invisibility—often the whole text or a substantial portion, such as an entire chapter. The only way to know for sure if the paper contained writing would be to shine a UV light over its surface. I made embroideries that rework conventions of handwriting on paper into hand-stitching on linen. Many of these pieces use an embroidered script derived from the old-fashioned Palmer method of cursive writing—once drilled into schoolchildren across the nation (including us), but now practically obsolete. In fact I was interested in a broad range of ways to make language material and transmissible, including Gregg shorthand, Morse code, printed type, embroidery alphabets, contemporary and historic handwriting samples, and digital typefaces that simulate handwriting. The texts themselves comment on various themes of invisibility, and feature passages from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, Herman Melville’s “The Tartarus of Maids,” The Invisible Man by H. G. Wells, Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino, Anne Carson’s The Albertine Workout, and others by Nabokov and George Eliot. Unlike Jeanne’s virtually unreadable writings, the texts in my embroideries are visibly attached to and pulled through surfaces of woven linen, materially rejoining text to its etymological sibling, textile. Some of these embroideries also employ glow-in-the-dark threads: in a reversal of the compromised legibility of Jeanne’s texts, which remain unreadable without the UV spectrum, my phosphorescent threads are plainly seen under normal lighting conditions but only fluoresce in darkness or with UV light. While we traded many books and texts back and forth—indeed, our shared love of reading was the foundation of the collaboration—each of us was free to choose the texts she most wanted to use, and throughout the process we constantly updated each other with progress reports. I love Stefan Zweig, and we were both so intrigued by his story “The Invisible Collector” that we made a collaborative piece—an embroidery framed in rubber, mounted on a rubber-coated easel. Jeanne then made another Zweig piece in rubber-cast braille. The installation at the Addison Gallery was conceived in a similar way, as a series of unfolding conversations, beginning with the interactive Ghost Library desks in the museum’s foyer. Together and in our respective contributions, we play with notions of how invisible thought becomes materialized. Each of us complicates the ancient, simple, yet laboriously learned skill of evincing language through handwriting: Jeanne writes invisibly, withholding or confusing readability; while my needle and thread retard the hand’s fluidity, painstakingly extending writing’s manual labor. Both of us engage in a kind of reverse transcription, privileging pre-modern forms of appropriation and compilation that purposely suspend the promised instantaneity of digital technologies. In reversing or frustrating the inscription and transmission of language, we hope to create a liminal space for looking, reading, and contemplation.

|